Rechtbank Den Haag, 26-05-2021, ECLI:NL:RBDHA:2021:5339, C/09/571932 / HA ZA 19-379 (engelse versie)

Rechtbank Den Haag, 26-05-2021, ECLI:NL:RBDHA:2021:5339, C/09/571932 / HA ZA 19-379 (engelse versie)

Gegevens

- Instantie

- Rechtbank Den Haag

- Datum uitspraak

- 26 mei 2021

- Datum publicatie

- 26 mei 2021

- ECLI

- ECLI:NL:RBDHA:2021:5339

- Formele relaties

- Hoger beroep: ECLI:NL:GHDHA:2024:2100, (Gedeeltelijke) vernietiging en zelf afgedaan

- Zaaknummer

- C/09/571932 / HA ZA 19-379 (engelse versie)

Inhoudsindicatie

The Hague District Court has ordered Royal Dutch Shell (RDS) to reduce the CO2 emissions of the Shell group by net 45% in 2030, compared to 2019 levels, through the Shell group's corporate policy.

ECLI nummer: ECLI:NL:RBDHA:2021:5337 (Dutch version)

Uitspraak

judgment

judgment

Commerce Team

case number / cause list number: C/09/571932 / HA ZA 19-379 (engelse versie)

Judgment of 26 May 2021

in the case of

1. the association VERENIGING MILIEUDEFENSIE, in Amsterdam, and THE OTHER PARTIES IT REPRESENTS,

2. the foundation STICHTING GREENPEACE NEDERLAND in Amsterdam,

3. the foundation STICHTING TER BEVORDERING FOSSIELVRIJ-BEWEGING in Amsterdam,

4. the association LANDELIJKE VERENIGING TOT BEHOUD VAN DE WADDENZEE in Harlingen,

5. the foundation STICHTING BOTH ENDS in Amsterdam,

6. the youth organization JONGEREN MILIEU ACTIEF in Amsterdam,

7. the foundation STICHTING ACTIONAID in Amsterdam,

claimants,

attorney-at-law mr. R.H.J. Cox of Maastricht

versus

ROYAL DUTCH SHELL PLC in The Hague,

defendant,

attorney-at-law mr. D. Horeman of Amsterdam.

Claimants are hereinafter jointly referred to as Milieudefensie et al. The claimants in the class action are individually referred to as Milieudefensie, Greenpeace Nederland, Fossielvrij NL, Waddenvereniging, Both Ends, Jongeren Milieu Actief and ActionAid. The 17,379 individual claimants who have issued to Milieudefensie a document appointing it as their representative ad litem are referred to as ‘the individual claimants’. The defendant is referred to as RDS.

1 The proceedings

The course of the proceedings is evidenced by the following:

- -

-

the summons of 5 April 2019, with Exhibits 1 through to 269;

- -

-

the statement of defence of 13 November 2019, with Exhibits RK-1 through to RK-30 and Exhibits RO-1 through to RO-250;

- -

-

the document containing additional exhibits of Milieudefensie et al. of 2 September 2020, with Exhibits 270 through to 331;

- -

-

the document containing exhibits of RDS of 2 September 2020, with Exhibits RK-31 through to RK-34 and Exhibits RO-251 through to RO-260;

- -

-

the document for a change of claim from Milieudefensie et al. of 21 October 2020;

- -

-

the notice of objection against the document for a change of claim of 28 October 2020 from RDS;

- -

-

the document containing additional exhibits of Milieudefensie et al. of 29 October 2020, with Exhibits 332 through to 336;

- -

-

the document containing exhibits of RDS of 30 October 2020, with Exhibits RK-35 and RK-36, and Exhibits RO-261 through to RO-280;

- -

-

the order of the cause list judge of 4 November 2020 on the objection against the change of claim, allowing the change of claim on the condition that Milieudefensie et al. provide a brief explanation on part 1(a) of the change of claim before 6 November 2020;

- -

-

the document containing an explanation of the change of the claim for relief 1A of Milieudefensie et al. of 6 November 2020;

- -

-

the reply to the explanation of the change of claim of Milieudefensie et al. from RDS, with Exhibit RO-281;

- -

-

the order of the cause list judge of 9 December 2020, declaring the objection of RDS against the alternative positions of Milieudefensie et al. unfounded;

- -

-

the document containing additional exhibits of 11 December 2020 of Milieudefensie et al., with Exhibit 337;

- -

-

the additional document containing exhibits of 15 December 2020 of RDS, with Exhibits RO-282 through to RO-284;

- -

-

the document containing additional exhibits of RDS of 16 December 2020, with Exhibit RK-37;

- -

-

the notice of objection against Exhibit RK-37 of Milieudefensie et al. of 16 December 2020;

- -

-

the reply to the notice of objection of RDS of 16 December 2020;

- -

-

the records of the oral hearings of 1, 3, 15 and 16 December 2020.

- -

-

the document of response to Exhibit RK-37 of Milieudefensie et al. of 30 December 2020, with Exhibits 338 and 339;

- -

-

the document commenting on the additional exhibits of RDS of 13 January 2021.

The records of the oral hearings were drawn up without the parties being present. The parties were given the opportunity to inform the court of factual inaccuracies. In a letter dated 19 February 2021, Milieudefensie et al. made use of this opportunity. In a letter dated 22 February 2021, RDS also made use of this opportunity. These letters form part of the case file.

Finally, the judgment date was scheduled for today.

2 The facts

In the finding of fact, the court starts from the developments up until 13 January 2021, the day on which the debate was closed . The facts are categorized as follows:

The claimants

RDS and the Shell group

Climate change and its consequences

Conventions, international agreements and policy intentions

Activities of RDS and the Shell group

Notice of liability of RDS from claimants

The claimants

Milieudefensie was founded on 6 January 1971 as the Raad voor Milieudefensie. Article 2 paragraph 1 and 2 of its articles of association are as follows:

“1. The object of the association is contributing to the solution and prevention of environmental problems and the conservation of cultural heritage, as well as striving for a sustainable society, at the global, national, regional and local level, in the broadest sense of the word, all of which in the interest of the association members and in the interest of the quality of the environment, nature and the landscape, in the broadest sense, for current and future generations.”

2. The association endeavours to attain its objects by: critically monitoring all those developments in society which affect the environment, nature, the landscape, and sustainability, influencing decision-making through using all appropriate and legitimate means, conducting research or having research conducted, disseminating and issuing information in the broadest sense, obtaining legal decisions, and performing all acts and actions the association deems necessary for attaining its objects.”

Greenpeace Nederland was founded in 1979. It works together with Greenpeace organizations established elsewhere. Article 4 paragraph 1 and 2 of its articles of association are as follows:

“1. The object of the foundation is promoting the conservation of nature.

2. Together with its supporters, staff and alliances the foundation endeavours to attain its objects by:

(...)

b. protecting biodiversity in all its forms;

c. combating climate change, and the pollution and abuse of the planet;

(...)

j. having and maintaining an office, and also performing all other actions connected to the foregoing in the broadest sense or which may be conducive to the foregoing.”

Fossielvrij NL was established on 22 March 2016. Article 3 paragraph 1 and 2 of its articles of association are as follows:

“3.1 The object of the foundation is as follows:

Promoting, protecting, supporting and accomplishing – at the local, regional and national level – social, environmental and economic justice and health for current and future generations by removing the social legitimacy of coal, oil and gas companies (so-called “fossil companies”) and effectuating the alternative use of investments and resources in order to expedite the transition to a sustainable economy which is based on renewable energy.

The foundation endeavours to attain this object by taking on all possible tasks which could promote its object. These include:

(...).

– Engaging in talks with staff and directors of organizations.

– Organizing, conducting and participating in creative actions and public campaigns.

– Showing what the foundation stands for and what it does by actively seeking out the public debate and approaching the media.

(...)

– Developing other types of activity.”

The articles of association of the association Waddenvereniging, established in 1965, state the following in Article 3 paragraph 1 and 2:

“1. The association strives for the conservation, restoration and proper management of the landscape and the environment and of the ecological and natural history values of the Wadden area, including but not limited to the northern sea-clay area, the Wadden islands, the Wadden Sea and the North Sea as irreplaceable and unique nature reserves. The association also aims to promote interest in these areas. The understanding that man forms part of the ecosystem is the foundation of the association’s actions.

2. The association endeavours to attain its object through all appropriate means, including:

– developing, effectuating and promoting activities for the protection of the ecological, environmental and cultural-historical value of and in the Wadden area, and standing up against activities that could harm the Wadden area;

– lobby activities and conducting legal actions;

(...)”

Both Ends was founded in 1986. Article 2 paragraph 1 and 2 of its articles of association are as follows:

“1. The object of the foundation is:

contributing to and promoting a responsible nature and environmental management across the globe, and also all that is connected, indirectly or directly, to this or which may be conducive to the foregoing, in the broadest sense of the word.

2. The foundation endeavours to attain its object, among other things, by:

(...)

b. actively strengthening and supporting organizations that integrate nature and environmental management aspects into activities of development cooperation and vice versa;

(...)”

Jongeren Milieu Actief was founded in 1990. Article 3 paragraph 1 and 2 of its articles of association are as follows:

“1. The object of the association is: striving for a better environment by:

a. a) creating a place for young people where they can be involved in sustainability in their own way;

b) actively working on the promotion of sustainability;

c) offering alternatives to live in a way that is more environmentally-friendly;

2. The association endeavours to attain its object by:

a. a) conducting campaigns and organizing activities, in the broadest sense, for and by young people;

b) using all legitimate means that are useful or necessary for its object.”

ActionAid was founded in 1997. Article 2 paragraph 1 and 2 of its articles of association are as follows:

“1. The object of the foundation is:

Contributing to the fight against poverty and injustice all over the world. Africa is an area of special focus.

Creating awareness and increasing the understanding among the public of the causes, effects and reasons for poverty and injustice.

Inducing policymakers to effectuate change in order to guarantee the rights of vulnerable and poor people.

(...)”

The 17,379 individual claimants have issued to Milieudefensie a document appointing it as their representative ad litem to claim on behalf of each of them that RDS reduces its emissions in line with the objective of the Paris Agreement.1

RDS and the Shell group

RDS is a public limited company, a legal person under private law, established under the laws of England and Wales. Its head office is established in The Hague.

Since the 2005 restructuring of the Shell group, RDS has been the top holding company of the Shell group. The Shell group is further composed of intermediate parents, Operating Companies and Service Companies. RDS is the direct or indirect shareholder of over 1,100 separate companies established all over the world. The Shell group develops activities worldwide. The Shell group such as existed before the 2005 restructuring is hereinafter referred to as ‘the then Shell group’.

The activities of RDS consists of holding shares in the intermediate parent companies, meeting its obligations with respect to shareholders based on its listings in New York, London and Amsterdam, and determining the group’s general corporate policy. The Operating Companies conduct operational activities and are responsible for implementing the general policy of the Shell group as determined by RDS. These Shell entities have assets and/or infrastructure with which they produce and trade in oil, gas or other energy sources. They also have permits for the exploitation, production or extraction of oil. The Service Companies provide assistance and services to the other group companies for the performance of their activities.

Climate change and its consequences

Mankind has been using energy, primarily produced by burning fossil fuels (coals, oil and gas), on a massive scale since the beginning of the Industrial Revolution. Carbon dioxide is released in this process. The chemical compound of the elements carbon and oxygen is designated with the chemical formula CO2. Some of the released CO2 is emitted into the atmosphere, where it lingers for hundreds of years, or even longer. Some of it is absorbed by the ecosystems of forests and oceans. This absorption option is steadily becoming smaller due to deforestation and the warming of sea water.

CO2 is the primary greenhouse gas which, together with other greenhouse gases, traps the heat emitted by the earth in the atmosphere. This is known as the greenhouse effect, which intensifies as more CO2 ends up in the atmosphere. This in turn increasingly warms the earth. The climate system has a delayed response to the greenhouse gas emissions: the warming effect of greenhouse gases which are emitted today will only become apparent in thirty to forty years’ time. Other greenhouse gases are, inter alia, methane, nitrous oxide and fluorinated gases. The unit ‘parts per million’ (hereinafter: ppm) is used to express the concentration of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. There is a direct, linear link between man-made greenhouse gas emissions, in part caused by the burning of fossil fuels, and global warming. The temperate of the earth has now increased

by about 1.1oC relative to the average temperature at the beginning of the Industrial Revolution. Over the past decades, global CO2 emissions have increased by 2% per year.

In climate science – the area of science that studies the climate and climate change – and in the international community there has been consensus for quite some time that the average temperature on earth should not increase by more than 2oC relative to the average temperature in the pre-industrial era. If the concentration of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere has stayed below 450 ppm by the year 2100, climate science believes there is a good chance that this target (hereinafter: the 2oC target) will be reached. In the last couple of years, further insight has shown that a safe temperature increase should not exceed 1.5oC with a corresponding greenhouse gas concentration level of no more than 430 ppm by the year 2100.

The current greenhouse gas concentration level is 401 ppm. The total global remaining capacity for further greenhouse gas emissions is also known as the carbon budget. Global CO2 emissions currently run at 40 Gt CO2 per year. Each year the global CO2 emissions stay at this level reduces the carbon budget by 40 Gt. If global CO2 emissions are higher, the carbon budget will decrease by more than 40 Gt. A carbon budget of 580 Gt CO2 was remained available from 2017 – a best estimate – for a 50% chance of a warming of 1.5oC.2 Now, three years later, 120 Gt CO2 of the carbon budget has been used, which means that 460 Gt CO2 remains. At unchanged emission levels, the carbon budget will have been used up within the foreseeable future.

The global effects of climate change are apparent from the reports of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (hereinafter: IPCC), the United Nations climate panel (see hereinafter under 2.4.4.).

In AR4 (IPCC Fourth Assessment Report, 2007), the IPCC explained that dangerous, irreversible climate change occurs if global warming exceeds 2oC. The report states that in order to have a more than 50% chance (‘more likely than not’) that the 2oC is not exceeded, the report explains that the concentration of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere has to stabilize at a level of about 450 ppm in 2100.

AR5 (IPCC Fifth Assessment Report, 2013-2014) describes that there is ‘likely’ (> 66%) chance for the rise in global temperature to remain below 2°C if the concentration of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere stabilizes at about 450 ppm in 2100. Stabilization at about 500 ppm in 2100 yields a chance of more than 50% (‘more likely than not’) of reaching the 2oC target. Only a limited number of studies have looked into scenarios that lead to a limitation of global warming to 1.5oC. Such scenarios are based on concentrations of under 430 ppm in 2100. In report AR5, the IPCC has categorized the key risks associated with anthropogenic climate change into five reasons for concern (RFC):

- -

-

RFC 1: Unique and threatened systems are both ecological and cultural systems. The global temperature rise will force certain human systems to make great adaptations or will cause ecosystems as we now know them, such as ice masses and coral reefs, to disappear.

- -

-

RFC 2: Extreme weather events will increase in both frequency and intensity. Drought, extreme precipitation, heat and (tropical) storms and hurricanes are examples of extreme weather events which are expected to increase and cause more forest fires (due to drought/heat) and floods (due to extreme precipitation and storms).

- -

-

RFC 3: Distribution of impacts: the consequences of climate change will be distributed unevenly in the world. The risks are distributed unevenly and in all countries, regardless of their development status, the impact of climate change will disproportionally affect the already weaker and marginalized groups, which will be the first to feel the impact on their food and water security.

- -

-

RFC 4: Global aggregate impacts are the effects of climate change which outstrip just the direct consequences and which are an accumulation of various indirect, mutually reinforcing effects. For example, climate change causes a loss of biodiversity, which will not only impact the ecology, but also the economy because people are dependent on biodiversity (fishery and agriculture).

- -

-

RFC 5: Large-scale singular events, or tipping points, are abrupt and drastic changes in physical, ecological or social systems which in most cases are irreversible and therefore have major and permanent consequences.3

The following are the key risks associated with the RFCs:

“i) Risk of death, injury, ill-health, or disrupted livelihoods in low-lying coastal zones and small island developing states and other small islands, due to storm surges, coastal flooding, and sea level rise. [RFC 1-5]

ii) Risk of severe ill-health and disrupted livelihoods for large urban populations due to inland flooding in some regions. [RFC 2 and 3]

iii) Systemic risks due to extreme weather events leading to breakdown of infrastructure networks and critical services such as electricity, water supply, and health and emergency services. [RFC 2-4]

iv) Risk of mortality and morbidity during periods of extreme heat, particularly for vulnerable urban populations and those working outdoors in urban or rural areas. [RFC 2 and 3]

v) Risk of food insecurity and the breakdown of food systems linked to warming, drought, flooding, and precipitation variability and extremes, particularly for poorer populations in urban and rural settings. [RFC 2-4]

vi) Risk of loss of rural livelihoods and income due to insufficient access to drinking and irrigation water and reduced agricultural productivity, particularly for farmers and pastoralists with minimal capital in semi-arid regions. [RFC 2 and 3]

vii) Risk of loss of marine and coastal ecosystems, biodiversity, and the ecosystem goods, functions, and services they provide for coastal livelihoods, especially for fishing communities in the tropics and the Arctic. [RFC 1, 2, and 4]

viii) Risk of loss of terrestrial and inland water ecosystems, biodiversity, and the ecosystem goods, functions, and services they provide for livelihoods. [RFC 1, 3, and 4]”

2.3.5.1. The SR15 report (IPCC Special Report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5°C, 2018) describes that the risks identified by the IPCC have increased:

“There are multiple lines of evidence that since AR5 the assessed levels of risk increased for four of the five Reasons for Concern (RFCs) for global warming to 2°C (high confidence). The risk transitions by degrees of global warming are now: from high to very high risk between 1.5°C and 2°C for RFC1 (Unique and threatened systems) (high confidence); from moderate to high risk between 1°C and 1.5°C for RFC2 (Extreme weather events) (medium confidence); from moderate to high risk between 1.5°C and 2°C for RFC3 (Distribution of impacts) (high confidence); from moderate to high risk between 1.5°C and 2.5°C for RFC4 (Global aggregate impacts) (medium confidence); and from moderate to high risk between 1°C and 2.5°C for RFC5 (Large-scale singular events) (medium confidence).” 4

2.3.5.2. In the SR15 report, the IPCC concludes that global warming will probably reach 1.5°C between 2030 and 2052 if the increase continues at the current level. Climate-related risks for man and nature will be higher than now with global warming at 1.5°C, but lower at 2°C. The risks hinge on the extent and rate of global warming, geographic location, development and vulnerability levels, and of choices in and implementation of adaptation and mitigation options. In order to limit global warming to 1.5°C, the report states that global emissions will have to have been reduced to far below 35 Gt Co2-eq by 2030. The IPCC also points out that half of the models used show that global emissions should be reduced to between 25 Gt and 30 Gt Co2-eq in 2030. The report states that, as a result of these findings, limiting global warming to 1.5°C requires a net reduction of 45% in global CO2 emissions in 2030 (bandwidth 40-60%) relative to 2010, and a net reduction of 100% in 2050 (bandwidth 2045-2055):

“In model pathways with no or limited overshoot of 1.5°C, global net anthropogenic CO2 emissions decline by about 45% from 2010 levels by 2030 (40–60% interquartile range), reaching net zero around 2050 (2045–2055 interquartile range). For limiting global warming to below 2°C CO2 emissions are projected to decline by about 25% by 2030 in most pathways (10–30% interquartile range) and reach net zero around 2070 (2065–2080 interquartile range). Non-CO2 emissions in pathways that limit global warming to 1.5°C show deep reductions that are similar to those in pathways limiting warming to 2°C. (high confidence).” 5

2.3.5.3. The SR15 report also states the following:

“All pathways that limit global warming to 1.5°C with limited or no overshoot project the use of carbon dioxide removal (CDR) on the order of 100–1000 GtCO2 over the 21st century. CDR would be used to compensate for residual emissions and, in most cases, achieve net negative emissions to return global warming to 1.5°C following a peak (high confidence). CDR deployment of several hundreds of GtCO2 is subject to multiple feasibility and sustainability constraints (high confidence). Significant near-term emissions reductions and measures to lower energy and land demand can limit CDR deployment to a few hundred GtCO2 without reliance on bioenergy with carbon capture and storage (BECCS) (high confidence).” 6

2.3.5.4. The SR15 report indicates with respect to the nationally determined contributions (NDCs) of the parties to the Paris Agreement that the NDCs are insufficient for limiting global warming to 1.5°C and that the target is only feasible if global CO2 emissions start to fall well before 2030:

“Estimates of the global emissions outcome of current nationally stated mitigation ambitions as submitted under the Paris Agreement would lead to global greenhouse gas emissions in 2030 of 52–58 GtCO2-eq yr−1 (medium confidence). Pathways reflecting these ambitions would not limit global warming to 1.5°C, even if supplemented by very challenging increases in the scale and ambition of emissions reductions after 2030 (high confidence). Avoiding overshoot and reliance on future large-scale deployment of carbon dioxide removal (CDR) can only be achieved if global CO2 emissions start to decline well before 2030 (high confidence).” 7

Europe

All parts of Europe will encounter the adverse effects of climate change. Individual citizens and companies will run a substantial financial risk as a result of these impacts.8 As a result of climate change Europe is expected to face more frequent heat waves, which will last longer and become more intense and result in more deaths.9 Human systems and ecosystems in Europe are vulnerable to climate change, but vulnerabilities will differ per region. The following applies to North-Western Europe:

“Coastal flooding has impacted low-lying coastal areas in north-western Europe in the past and the risks are expected to increase due to sea-level rise and an increased risk of storm surges. North Sea countries are particularly vulnerable, especially Belgium, Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom. Higher winter precipitation is projected to increase the intensity and frequency of winter and spring river flooding, although to date no increased trends in flooding have been observed.” 10

The Netherlands

The Netherlands has relatively high per capita CO2 emissions compared to other industrialized countries. The impacts of global warming (globally about 0.8 degrees higher than pre-industrial temperatures and 1.7 degrees in the Netherlands) are already noticeable in the Netherlands.11 Heat waves, drought, floods, damage to ecosystems, threat to food production and damage to health are expected to intensify in future if the global average temperature rises. According to the Royal Netherlands Meteorological Institute (KNMI)12, in the future the Netherlands will have to take account of higher temperatures, a faster rising sea level, wetter winters, heavier precipitation and chances of drier summers. The KNMI states the following, inter alia:

“In climate science it is accepted that a large degree of global warming will increase the risk of a major abrupt transition in the climate system. However there is as of yet no firm quantitative basis for the direction and magnitude of such a transition. Therefore, developing such transitions into extreme scenarios is beyond the scope of KNMI’14. Nevertheless, some examples have been provided below. Some climate models indicate a slow but complete shut down of the warm Gulf Stream before 2100. This reduces the warming over Europe in all but one of these models, in which the Gulf Stream shuts down around 2050 and Europe even sees a temporary net cooling. A few models indicate an abrupt decline in Arctic sea-ice cover during warming scenarios, resulting in a strong temperature increase over the North Pole area. This may impact the formation of storms that affect Europe. Another effect featured in some climate models is a much stronger drying of the soil in southern Europe. This ‘desertification’ of the Mediterranean will favour easterly winds over the Netherlands, leading to very warm and dry summers. There are two other relevant processes that are either not included or not well represented in current climate models. The first is a collapse of the West Antarctic ice sheet. At present this ice sheet is losing mass by increased iceberg calving. Once a collapse has been initiated, for which no indications exist at present, the mass loss might be much greater than accounted for in the KNMI’14 sea-level rise scenarios. The second process is the possibility of remnants of tropical hurricanes hitting Europe. Observations show that over the last two decades Atlantic hurricanes form more often in the eastern Tropics compared to the Caribbean. A large proportion of these hurricanes move directly to the north, and travel to Western Europe. The chances of Atlantic hurricanes to form in the eastern Tropics will increase due to global warming, and therefore also the probability of remnants of hurricanes hitting Western Europe. New experiments performed by KNMI with a highly detailed climate model have confirmed this. It will result in an earlier and more severe storm season in the Netherlands.” 13

According to the KNMI, a sea level rise of 2.5 to 3m this century cannot be ruled out. If global warming does not exceed 2°C this century, it is possible that the sea level rise remains limited from 0.3 to at most 2.0m. However, if the global warming is greater (4°C in 2100) the sea level rise may climb to 2.0m and 3.0m at most in 2100. After 2100, this accelerated sea level rise may increase to 5m and possibly 8m in 2200. After 2050, the sea level rise is expected to accelerate even further. To counter this, various measures have to be taken, including faster and increased sand nourishment along the coast, strengthening or replacing storm surge barriers and other flood risk management works in a shorter term than currently envisioned, and moving and enlarging fresh water inlets.14 Up to 2030, the impact of an accelerated sea level rise will be limited and hardly noticeable in the Dutch Wadden Sea. However, in the long term, up to the year 2100, the anticipated change will depend to a great extent on the climate scenarios, varying from hardly any impact up to 2100 to a noticeable impact in 2050. In most scenarios, none of the tidal basins in the Dutch Wadden Sea will have drowned by 2100. In the more extreme scenario (DeConto & Pollard), which predicts a total sea level rise of approximately 1.7m in 2100, the Wadden Sea will drown before 2100.15

Climate change-related health problems in Dutch residents include heat stress, increasing infectious diseases, deterioration of air quality, increase of UV exposure, and an increase of water-related and foodborne diseases. In the coming decades, the Netherlands will also face many water-related climate impacts, such as flooding along the coast and rivers, excess water, water shortage, deterioration of water quality, salinization, raised water levels and drought. Periods of either drought and water shortage or problems due to excess water may occur on an annual basis. These changes and uncertainties in water availability will have an impact on agriculture and biodiversity, but also on, for example, the energy sector and the manufacturing industry, for instance in the form of cooling water problems and poor accessibility via rivers in case of drought and network problems due to drought, excess water or other weather extremes).16

Conventions, international agreements and policy intentions

A UN conference on ‘Human environment’ was held in Stockholm in 1972. The conference brought forth the Stockholm Declaration, in which the principles of international environmental policy and environmental law were laid down. The United Nations Environment Program (UNEP) was established as a result of the conference.

The UN Climate Convention

In 1992 the UN Climate Convention (a framework convention) was concluded. This convention has since entered into force and ratified by the majority of the global community, including the Netherlands. The convention seeks to protect the planet’s ecosystems and mankind and strives for sustainable development for the protection of current and future generations. The preamble to the convention contains the following consideration, inter alia: “Determined to protect the climate system for present and future generations”. Article 2 of the convention reads as follows:

“The ultimate objective of this Convention and any related legal instruments that the Conference of the Parties may adopt is to achieve, in accordance with the relevant provisions of the Convention, stabilization of greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere at a level that would prevent dangerous anthropogenic interference with the climate system. Such a level should be achieved within a time frame sufficient to allow ecosystems to adapt naturally to climate change, to ensure that food production is not threatened and to enable economic development to proceed in a sustainable manner.”

Article 7 has established the Conference of the Parties (hereinafter: COP), which usually convenes every year (the so-named climate change conferences). The COP is the highest decision-making entity under the convention, although COP decisions are not legally binding. Numerous COPs (climate change conferences) have since been held, including the COP 21 in 2015 in Paris (the Paris Climate Conference), culminating in the Paris Agreement, the COP 22 in 2016 in Marrakesh, in which the parties called for more ambition and a more intensive cooperation to close the gap between the current emissions reduction targets and the targets of the Paris Agreement and for further climate actions, and the COP 25 in 2019 in Madrid (see below under 2.4.8).

The IPCC

In 1988, the UNEP and the World Meteorological Organization (WMO), under the auspices of the United Nations, established the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). The IPCC focuses on gaining insight into all aspects of climate change through scientific research. It does not carry out its own research, but rather studies and assesses the most recent scientific and technical information that is made available worldwide. The IPCC is not just a scientific but also an intergovernmental organization. It has 195 members, including the Netherlands. Since its establishment, the IPCC has published five reports (Assessment Reports), with associated specialist reports, on the state of affairs in climate science and on climate developments. (See under 2.3.5.1 through to 2.3.5.4).

The UNEP

The UNEP has issued annual reports on the so-named emissions gap since 2010. The emissions gap is the difference between the desired emissions level in a particular year and the reduction targets to which the relevant countries committed. In UNEP’s annual report on the year 2013, it was found for the third time in a row that the pledges had fallen short and greenhouse gas emissions had seen a rise rather than a drop. In its 2017 report, the UNEP noted that if the emissions gap is not bridged in 2030, it is highly unlikely that the 2°C target will be reached. Even if the reduction targets underlying the Paris Agreement are implemented in fully, 80% of the carbon budget remaining in the context of the 2°C target will be used by 2030. If a 1.5°C target is taken as a basis, the associated carbon budget will have been completely used up by then.

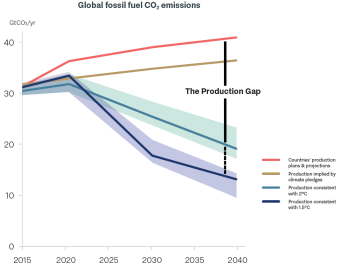

The 2019 UNEP Production Gap Report focuses on the so-called production gap. This gap is the difference between the planned production of fossil fuels of countries and global production levels in line with global warming limited to 1.5°C or 2°C. The following conclusion was drawn in this report, inter alia:

“In aggregate, countries’ planned fossil fuel production by 2030 will lead to the emission of 39 billion tonnes (gigatonnes) of carbon dioxide (GtCO2). That is 13 GtCO2, or 53%, more than would be consistent with a 2°C pathway, and 21 GtCO2 (120%) more than would be consistent with a 1.5°C pathway. This gap widens significantly by 2040.

(...)

Oil and gas are also on track to exceed carbon budgets, as countries continue to invest in fossil fuel infrastructure that “locks in” oil and gas use. The effects of this lock-in widen the production gap over time, until countries are producing 43% (36 million barrels per day) more oil and 47% (1,800 billion cubic meters) more gas by 2040 than would be consistent with a 2°C pathway.” 17

Below is a diagram of the production gap18:

The Paris Agreement

The Paris Agreement, which was signed on 22 April 2016, entered into effect on 4 November 2016, and covering the period from 2020, has a different system than the UN Climate Convention. Each country is called to account regarding its individual responsibility (bottom-up approach). In short, the following is laid down in the agreement, inter alia:

- -

-

Global warming must be kept well below the 2oC threshold relative to the pre-industrial age, while striving for 1.5°C.

- -

-

The parties have to draw up national climate plans, namely nationally determined contributions (NDCs), which must be ambitious and whose ambition level must increase with each new plan.

- -

-

The parties observe with great concern that the current NDCs are insufficient for an average temperature rise of no more than 2oC relative to the pre-industrial age.

- -

-

The use of fossil fuels must be brought to an end quickly, as this is a major cause of excessive CO2 emissions.

The decision of the parties to adopt the Paris Agreement notes the following about non-state stakeholders:

“The Conference of the Parties

(...)

117. Welcomes the efforts of non-Party stakeholders to scale up their climate actions, and

encourages the registration of those actions in the Non-State Actor Zone for Climate

Action platform;

(...)

133. Welcomes the efforts of all non-Party stakeholders to address and respond to climate

change, including those of civil society, the private sector, financial institutions, cities and

other subnational authorities;

134. Invites the non-Party stakeholders referred to in paragraph 133 above to scale up

their efforts and support actions to reduce emissions and/or to build resilience and decrease

vulnerability to the adverse effects of climate change and demonstrate these efforts via the

Non-State Actor Zone for Climate Action platform referred to in paragraph 117 above;”

During the 25th Conference of the Parties in Madrid in 2019 (COP 25) held under the UN Climate Convention, the so-called Climate Ambition Alliance was established. In the Climate Ambition Alliance, both state and non-state actors have signalled their intention to achieve net-zero CO2 emissions by 2050, required to meet the climate goals of the Paris Agreement. The press release on this alliance of state and non-state actors mentions, among other things, that countries cannot take on this task on their own, that non-state action is required for meeting the goal of the Paris Agreement, and that this needs to be done with due observance of the latest scientific findings. Under the auspices of the UN, the so-called Race to Zero initiative was developed in order to achieve the necessary expansion of the group of non-state actors in the Climate Ambition Alliance in the quickest way possible. The Race to Zero initiative is an assembly of global networks that have developed emissions reduction protocols and guidelines for non-state actors. Based on scientific findings, these protocols and guidelines present, inter alia, what companies should do to reduce the greenhouse gas emissions caused by their activities and products.

The International Energy Agency (IEA)

The International Energy Agency (IEA) is an intergovernmental organization that was established in 1974 in order to support the coordination of a collective response to major disruptions in the oil supply. The IEA has 30 member countries, including the Netherlands. Although the oil supply forms a substantial focus area of the IEA, the agency has also focused its attention on other sources of energy. In its Beyond 2 Degree-Scenario (B2DS), the IEA assumes a reduction of 21 to 22 Gt CO2 in 2030. This represents a 35% drop relative to the starting point of 33 Gt in 2014, which the IEA uses as a base year.19

The IEA has published its annual World Energy Outlook since 1977. It offers analyses and insights into developments in the energy market and what these developments signify for energy certainty, environmental protection and economic developments.

In its World Energy Outlook 2019, the IEA foresees that the demand for oil and natural gas will rise until 2040 across all scenarios outlined in the outlook. The IEA distinguishes three scenarios, namely the Current Policies Scenario, the Stated Policies Scenario and the Sustainable Development Scenario (SDS). The IEA explains these scenarios as follows in the World Energy Outlook 2019:

“ The Current Policies Scenario shows what happens if the world continues along its present path, without any additional changes in policy. In this scenario, energy demand rises by 1.3% each year to 2040, with increasing demand for energy services unrestrained by further efforts to improve efficiency. While this is well below the remarkable 2.3% growth seen in 2018, it would result in a relentless upward march in energy-related emissions, as well as growing strains on almost all aspects of energy security.

The Stated Policies Scenario, by contrast, incorporates today’s policy intentions and targets. Previously known as the New Policies Scenario, it has been renamed to underline that it considers only specific policy initiatives that have already been announced. The aim is to hold up a mirror to the plans of today’s policy makers and illustrate their consequences, not to guess how these policy preferences may change in the future.

In the Stated Policies Scenario, energy demand rises by 1% per year to 2040. Low-carbon sources, led by solar photovoltaics (PV), supply more than half of this growth, and natural gas, boosted by rising trade in liquefied natural gas (LNG), accounts for another third. Oil demand flattens out in the 2030s, and coal use edges lower. Some parts of the energy sector, led by electricity, undergo rapid transformations. Some countries, notably those with “net zero” aspirations, go far in reshaping all aspects of their supply and consumption. However, the momentum behind clean energy technologies is not enough to offset the effects of an expanding global economy and growing population. The rise in emissions slows but, with no peak before 2040, the world falls far short of shared sustainability goals.

The Sustainable Development Scenario maps out a way to meet sustainable energy goals in full, requiring rapid and widespread changes across all parts of the energy system. This scenario charts a path fully aligned with the Paris Agreement by holding the rise in global temperatures to “well below 2°C ... and pursuing efforts to limit [it] to 1.5°C”, and meets objectives related to universal energy access and cleaner air. The breadth of the world’s energy needs means that there are no simple or single solutions. Sharp emission cuts are achieved across the board thanks to multiple fuels and technologies providing efficient and cost-effective energy services for all.”

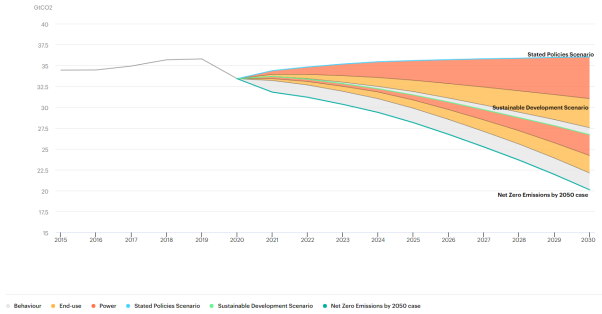

In the World Energy Outlook 2020, published in October 2020, the IEA introduces the ‘Net Zero Emissions by 2050 (NZE2050) case’, which is a translation of a net zero scenario in 2050 for the energy sector. The IEA notes the following, inter alia:

“Decisions over the next decade will play a critical role in determining the pathway to 2050. For this reason, we examine what the NZE2050 would mean for the years through to 2030. Total CO2 emissions would need to fall by around 45% from 2010 levels by 2030, meaning that energy sector and industrial process CO2 emissions would need to be around 20.1 Gt, or 6.6 Gt lower than in the SDS in 2030.” 20

The outlook contains the below graph, entitled ‘Energy and industrial process CO2 emissions and reduction levers in WEO 2020 scenarios, 2015-2030’21:

The European Union (EU)

Article 191 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU) contains the EU’s environmental goals. For the implementation of its environmental policy, the EU has worked out a large number of directives, including the so-named 2013 ETS directive (Directive 2003/87/EC), which was subsequently amended. The Directive has established a scheme for greenhouse gas emission allowance trading in the EU. Overall, the ETS system works as follows. Companies in the EU that fall under the ETS system, which are energy-intensive companies such as those in the energy sector, may only emit greenhouse gases in exchange for surrendering emission allowances. The allowances can be purchased, sold or kept. The system currently provides for an emissions reduction of 43% by 2030 relative to 2005.22 On 17 September 2020, the European Commission proposed a new EU reduction target of at least 55% in all sectors by 2030 relative to 1990.23 The European Council discussed this enhancement on 15 October 2020.

The Netherlands

In proceedings instituted by Urgenda, a foundation and citizens’ group that focuses on developing plans and measures for the prevention of climate change, the Dutch State was ordered to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by at least 25% as of late 2020 relative to 1990.24

On 28 June 2019, the Dutch cabinet presented its Climate Agreement. The Climate Agreement encompasses a package of measures and agreement between companies, social organizations and government bodies for the joint reduction of greenhouse gas emissions in the Netherlands by 49% in 2030 relative to 1990. The Climate Agreement is the result of consultations among some 150 parties, which gathered at five environment-themed round table meetings, namely Electricity, Industry, Built Environment, Agriculture and Mobility. The implementation of the agreements will be run wherever possible by the participating parties, including the central government.

On 1 September 2019, the Climate Act25 entered into force. This act provides a framework for the development of policy geared towards a permanent and gradual reduction of greenhouse gas emissions in the Netherlands to a level that will be 95% lower in 2050 than in 1990, with the purpose of curbing global warming and climate change. The aim is to achieve a 49% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions by 2030 and a full Co2-neutral electricity production by 2050 in order to meet the target for 2050. According to the Climate Act, the cabinet must draw up a Climate Plan. The first Climate Plan is based on the Climate Agreement and covers the period between 2021 and 2030. The plan contains the broad outlines with which the cabinet seeks to achieve the targets in the Climate Act as well as a number of considerations, including on the latest scientific insights in the area of climate change and on the economic impact of the policy.

Activities of RDS and the Shell group

As the top holding company, RDS establishes the general policy of the Shell group. For instance, RDS draws up the investment guidelines in support of the energy transition as well as the business principles for the Shell companies. RDS reports on the consolidated performance of the Shell companies and maintains relationships with investors. In RDS’ Sustainability Report 2019, the RDS Board is designated in a ‘Climate Change Management Organogram’ as having ‘oversight of climate change risk management’. The companies of the Shell group are responsible for the implementation and execution of the general policy. They must adhere to the applicable legislation and their contractual obligations. Each Shell company bears operational responsibility for the implementation of ‘climate change policies and strategies’.

RDS has made executive remuneration dependent on reaching short-term targets. In the 2019 Annual Report it was reported that the performance indicator ‘energy transition’ counts towards 10% in the weighting. The other 90% is linked to other, mostly financial performance indicators.

As the top holding company, RDS reports on the greenhouse gas emissions of the various Shell companies, both on the basis of the relevant company’s operational control (100% of the emissions of companies and joint ventures operated by one of the Shell companies) as well as on the basis of the relevant company’s share capital (equity share of the emissions of companies and joint ventures in which Shell participates).

RDS reports on greenhouse gas emissions on the basis of the World Resources Institute Greenhouse Gas Protocol (GHG Protocol). The GHG Protocol categorizes greenhouse gas emissions in Scope 1, 2 and 3:

- -

-

Scope 1: direct emissions from sources that are owned or controlled in full or in part by the organization;

- -

-

Scope 2: indirect emissions from third-party sources from which the organization has purchased or acquired electricity, steam, or heating for its operations;

- -

-

Scope 3: all other indirect emissions resulting from activities of the organization, but occurring from greenhouse gas sources owned or controlled by third parties, such as other organizations or consumers, including emissions from the use of third-party purchased crude oil and gas.

RDS’ reporting method and Shell’s information on greenhouse gas emissions are available, inter alia, in their annual reports, Sustainability Reports, the Carbon Disclosure Project (CDP) – an international not-for-profit charity that runs the global disclosure system for investors, companies, cities, states and regions – and on the website of the Shell group. In 2018, RDS reported that 85% of the Shell group emissions were Scope 3 emissions.

In its 2019 submission to the CDP, RDS writes that its CEO has ultimate responsibility for the general management of the Shell group. The CEO is the most senior individual who is ultimately accountable for all management, except with respect to matters falling under the ultimate responsibility of the RDS Board or which belong to the domain of the RDS shareholders’ meeting. With respect to climate change, the following is stated in the submission to the CDP:

“The CEO is the most senior individual with accountability for climate change. This includes the delivery of Shell ́s strategy, e.g. through Shell ́s plans (...) to set short-term targets for reducing the Net Carbon Footprint of the energy products it sells (...).”

The 2019 CDP submission explains that the climate policy, for which the RDS CEO bears ultimate accountability, is adopted by the RDS Board, which has ‘oversight of climate-related issues’. Among its ‘governance mechanisms into which climate-related issues are integrated’ are ‘Setting performance objectives; Monitoring; implementation and performance of objectives; Overseeing major capital expenditures, acquisitions and divestitures; Monitoring and overseeing progress against goals and targets for addressing climate-related issues’. The RDS Board seeks the advice of a so-called Board-level committee, namely the Corporate and Social Responsibility Committee (CSRC). The role of the CSRC is as follows:

“(...) to review and advise the Board on Shell's strategy, policies and performance in the areas of safety, environment, ethics and reputation against the Shell General Business Principles, the Shell Code of Conduct, and the HSSE & SP Control Framework. Conclusions/recommendations made by the CSRC are reported directly to the Executive Committee and Board. The topics discussed in depth included personal and process safety, road safety, the energy transition and climate change, Shell’s Net Carbon Footprint ambition, the Company’s environmental and societal licence to operate, and its ethics programme.”

The 2019 submission to the CDP also states the following:

“Climate change and risks resulting from GHG emissions have been identified as a significant risk factor for Shell and are managed in accordance with other significant risks through the Board and Executive Committee. Shell's processes for identifying, assessing, and managing climate-related issues are integrated into our overall multi-disciplinary company-wide risk identification, assessment and management process. Shell frequently monitors and assesses climate-related risks looking at different time horizons; short (up to 3 years), medium (three years up to around 10 years) and long term (beyond around 10 years). Shell has a climate change risk management structure in place which is supported by standards, policies and controls.

(...)

Finally, we assess our portfolio decisions, including divestments and investments, against potential impacts from the transition to lower-carbon energy. These include higher regulatory costs linked to carbon emissions and lower demand for oil and gas. The portfolio changes we are making reduce the risk of having assets that are uneconomic to operate, or oil and gas reserves that are uneconomic to produce because of changes in demand or CO2 regulations.”

In 1988, the then Shell group published an internal report on climate change, which had been drawn up in 1986, entitled ‘The Greenhouse Effect’. In it, and in the information film, ‘Climate of concern’, the then Shell group warned about the dangers of climate change. In a brochure with the title ‘Climate Change, what does Shell think and do about it’ from March 1998, the following is stated about the role of the then Shell group in changing energy markets:

“They must play their part in the necessary precautionary measures to limit greenhouse gas emissions.

Shell companies expect to do the following:

(...)

Reduce emissions of greenhouse gases in their own operations as well as helping their customers to do the same.”

In 1998, a new branch, known as the Shell International Renewables, was created in the then Shell group, whose focus was on new forms of energy, including solar energy, the planting of forests, and energy from biomass.

From 2006/2007 onward, the Shell group invested in tar sand in Canada in order to extract tar sand oil. The Shell company in question, Shell Canada, sold some parts of this investment in 2017. From late 2017/January 2018, the Shell group started to focus on the extraction of oil and gas from shale, which requires a drilling technique known as fracking. It is an intensive process that costs extra energy and consequently may culminate in a higher CO2 emission per unit of energy generated as compared to the conventional extraction of petroleum and natural gas. Moreover, the extraction of shale gas and shale oil, it turns out, releases the highly potent greenhouse gas methane into the atmosphere.

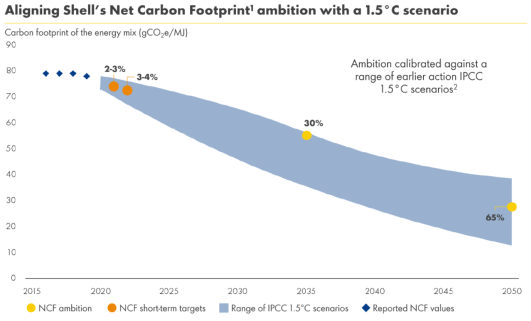

In December 2017, RDS presented its ‘Net Carbon Footprint Ambition’ (NCF ambition) for the Shell group. The NCF ambition is a long-term ambition with which the Shell group seeks to reduce the CO2 intensity of the energy products sold by the group by 2050. It is an intensity-based standard which focuses on the Shell group’s relative contribution to the emissions reduction in the total energy system. The NCF ambition pertains to a reduction of the CO2 intensity of Scope 1, 2 and 3 emissions. The NCF ambition is generally adjusted very five years. In 2019, RDS also started to use targets, in addition to ambitions, for the short term for the Shell group, such as a specific NCF target. The short-term targets will be established every year for a period of three to five years. RDS annually reports on the NCF ambition in its Sustainability Report. The website of the Shell group also states the following about the NCF ambition:

“Our ambition depends on society making progress to meet the Paris Agreement. If society changes its energy demands more quickly, we intend to aid that acceleration. If it changes more slowly, we will not be able to move as quickly as we would like. Both energy demand and energy supply must evolve together. This is because no business can survive unless it sells things that people need and buy.” 26

In 2018, RDS published the Sky Report containing the ‘Sky’ scenario (hereinafter: Sky) for the development of future energy systems. RDS uses this scenario, inter alia, to support and test its business decisions. Sky assumes that society will reach net zero emissions by 2070, which means that the target of the Paris Agreement of keeping the global average temperature rise well below 2°C will have been met. Sky assumes a swift growth of renewable energy sources, such as wind and solar, and of low-emission fuels, such as biofuels, in addition to a persisting demand for oil and gas in the long term. Sky also foresees a substantial increase of a method for capturing and re-using CO2, known as Carbon Capture Utilization and Storage (CCUS), to further limit CO2 emissions in the atmosphere. Sky assumes that even in a climate-neutral energy system, with net zero CO2 emissions in 2070, fossil fuels – if combined with CCUS – still constitute 22% of the total energy supply, of which oil and gas form 16%. In 2050, this could be 45%, of which oil and gas form 33%. The report also states the following:

“From 2018 to around 2030, there is clear recognition that the potential for dramatic short-term change in the energy system is limited, given the installed base of capital across the economy and available technologies, even as aggressive new policies are introduced.”

In 2018, RDS published the Energy Transformation Report 2018, which was intended to answer questions of shareholders, governments and not-for-profit organizations about the significance of the energy transition for the Shell group. The report states, among other things, that in all scenarios used by RDS, including the Sky scenario, the demand for oil and natural gas will be higher in 2030 than in 2018 and:

“To meet that demand, we expect to make continued investments in finding and producing oil and gas.”

The report also states that the Shell group also invests in other energy sources, such as hydrogen, biofuels and wind, and that the Shell group wants to lower the CO2 intensity of its products.

The report states the following regarding the risk of so-called ‘stranded assets’:

“LOW RISK OF STRANDED ASSETS

Every year, we test our portfolio under different scenarios, including prolonged low oil prices. In addition, we rank the break-even prices of our assets in the Upstream 27 and Integrated Gas businesses to assess their resilience against low oil and gas prices. These assessments indicate that the risk of stranded assets in the current portfolio is low.

At December 31, 2017, we estimate that around 80% of our current proved oil and gas reserves, will be produced by 2030 and only around 20% after that time. Production that is already on stream will continue as long as we cover our marginal costs.

We also estimate that around 76% of our proved plus probable oil and gas reserves, known as 2P, will be produced by 2030, and only 24% after that time.”

The disclaimer at the end of the Energy Transformation Report 2018 states the following:

“Additionally, it is important to note that Shell’s existing portfolio has been decades in development. While we believe our portfolio is resilient under a wide range of outlooks, including the IEA’s 450 scenario (World Energy Outlook 2016), it includes assets across a spectrum of energy intensities including some with above-average intensity. While we seek to enhance our operations’ average energy intensity through both the development of new projects and divestments, we have no immediate plans to move to a net-zero emissions portfolio over our investment horizon of 10-20 years. Although, we have no immediate plans to move to a net-zero emissions portfolio, in November of 2017, we announced our ambition to reduce the Net Carbon Footprint of the energy products we sell in accordance with society’s implementation of the Paris Agreement’s goal of holding global average temperature to well below 2°C above pre industrial levels. Accordingly, assuming society aligns itself with the Paris Agreement’s goals, we aim to reduce our Net Carbon Footprint, which includes not only our direct and indirect carbon emissions, associated with producing the energy products which we sell, but also our customers’ emissions from their use of the energy products that we sell, by 20% in 2035 and by 50% in 2050.”

In October 2018, the CEO of RDS said the following in a speech:

“Shell’s core business is, and will be for the foreseeable future, very much in oil and gas, and particularly in natural gas [...] people think we have gone soft on the future of oil and gas. If they did think that, they would be wrong.”

On 12 September 2019, Shell Nederland, part of the Shell group, and several other organizations, signed the Climate Agreement.

In response to the more far-reaching ambition of the European Commission to become climate neutral by 2050 (‘the Green Deal’), RDS issued a sketch in 2020 entitled ‘A climate-Neutral EU by 2050’, in which it notes that the EU ambitions require an acceleration of the energy transition that goes beyond the Sky scenario. RDS emphasizes that in order to facilitate the energy transition, the EU must create a policy framework with clear and binding legislative targets. RDS also explains in the sketch that carbon pricing must be expanded across the economy.

RDS included the adjusted ambitions for the Shell group in its ‘Responsible Investment Annual Briefing’ of April 2020 (hereinafter: ‘RI Annual Briefing van 2020’), aimed at its investors. In the briefing, RDS states that the Shell group strives for a reduction of CO2 emissions to net zero in 2050, or sooner from the manufacture of all its products, or all of Scope 1 and 2 emissions. With regard to Scope 3 emissions, RDS wants to reduce the CO2 intensity of the Shell group’s energy products per sold unit of energy (the NCF) by 30% in 2035 (was: 20%) and by 65% in 2050 (was: 50%). RDS also wants to help customers of the Shell group reduce their use of Shell energy products, the Scope 3 emissions, to net zero in 2050 or sooner. Finally, RDS has formulated short-term targets for the next two to three years.

In its RI Annual Briefing of 2020 (hereinafter: ‘the RI Annual Briefing 2020’), RDS shows in a diagram how it believes its ambitions for the Shell group, both in the short and long term, relate to the so-called ‘earlier action’ IPCC 1.5°C scenarios:

The RI Annual Briefing 2020 contains the following warning (‘Definitions and cautionary note’), inter alia:

“Additionally, it is important to note that as of April 16, 2020, Shell’s operating plans and budgets do not reflect Shell’s net-zero emissions ambition. Shell’s aim is that, in the future, its operating plans and budgets will change to reflect this movement towards its new net-zero emissions ambition. However, these plans and budgets need to be in step with the movement towards a net-zero emissions economy within society and among Shell’s customers. Also, in this presentation we may refer to “Shell’s Net Carbon Footprint”, which includes Shell’s carbon emissions from the production of our energy products, our suppliers’ carbon emissions in supplying energy for that production and our customers’ carbon emissions associated with their use of the energy products we sell. Shell only controls its own emissions but, to support society in achieving the Paris Agreement goals, we aim to help and influence such suppliers and consumers to likewise lower their emissions.”

At the presentation of the third-quarter figures, on 29 October 2020, RDS gave a brief explanation of the Shell group’s strategic direction during the presentation of the third quarter figures. Its strategic direction is as follows:

“Shell will reshape its portfolio of assets and products to meet the cleaner energy needs of its customers in the coming decades. The key elements of Shell’s strategic direction include:

▪ Ambition to be a net-zero emissions energy business by 2050 or sooner, in step with society and its customers.

▪ Grow its leading marketing business, further develop the integrated power business and commercialise hydrogen and biofuels to support customers’ efforts to achieve net-zero emissions.

▪ Transform the Refining portfolio from the current fourteen sites into six high-value energy and chemicals parks, integrated with Chemicals. Growth in Chemicals will pivot to more performance chemicals and recycled feedstocks.

▪ Extend leadership in liquefied natural gas (LNG) to enable decarbonisation of key markets and sectors.

▪ Focus on value over volume by simplifying Upstream to nine significant core positions, generating more than 80% of Upstream cash flow from operations.

▪ Enhanced value delivery through Trading and Optimisation.”

The website of the Shell group also states the following:

“We have the responsibility and commitment to respect human rights with a strong focus on how we interact with communities, security, labour rights and supply chain conditions.”

(...)

We are committed to respecting human rights. Our human rights policy is informed by the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights and applies to all our employees and contractors.”

In an open letter to the shareholders dated 16 May 2014, RDS wrote the following:

“We are writing this letter in response to enquiries from shareholders regarding the “carbon bubble” or “stranded assets” issue [...] there is a high degree of confidence that global warming will exceed 2°C by the end of the 21st century [...] because of the long-lived nature of the infrastructure and many assets in the energy system, any transformation will inevitably take decades [...] Shell does not believe that any of its proven reserves will become “stranded” as a result of current or reasonably foreseeable future legislation concerning carbon.”

Since 2016, the Dutch NGO Follow This, shareholder in RDS, has submitted various resolutions with the request to exchange the investments of the Shell group in oil and gas for sustainable energy. The RDS Board has consistently recommended its shareholders to vote against these resolutions for being contrary to the company’s interests. The RDS Board stated the following, among other things:

“tying the Company’s hands to a renewables only mandate would be strategically and commercially unwise.”

The majority of shareholders has voted against these resolutions.

Notice of liability of RDS from claimants

In a letter dated 4 April 2018, Milieudefensie held RDS liable for its current policy as well as claimed conformity with the climate targets under the Paris Agreement. RDS responded in a letter dated 28 May 2018 stating that the claims of Milieudefensie were unfounded, that the courts were not the appropriate forum for questions about the energy transition, and that the approach of Milieudefensie was not constructive.

In a letter dated 12 February 2019, Milieudefensie et al. gave RDS another opportunity to comply with what had been claimed earlier, which RDS rejected in a letter dated 26 March 2019.

3 The dispute

Milieudefensie et al. claim, following a change of claim, (in essence) for the court:

1. to rule:

- -

-

a) that the aggregate annual volume of CO2 emissions into the atmosphere (Scope 1, 2 and 3) due to the business operations and sold energy products of RDS and the companies and legal entities it commonly includes in its consolidated annual accounts and with which it jointly forms the Shell group constitutes an unlawful act towards Milieudefensie et al. and (i) that RDS must reduce this emissions volume, both directly and via the companies and legal entities it commonly includes in its consolidated annual accounts and with which it jointly forms the Shell group, and (ii) that this reduction obligation must be achieved relative to the emissions level of the Shell group in the year 2019 and in accordance with the global temperature target of Article 2 paragraph 1 under a of the Paris Agreement and in accordance with the related best available (UN) climate science.

- -

-

b) that RDS acts unlawfully towards Milieudefensie et al. if RDS, both directly and via the companies and legal entities it commonly includes in its consolidated annual accounts and with which it jointly forms the Shell group:

- principally: fails to reduce or cause to be reduced by at least 45% or net 45% relative to 2019 levels, no later than at year-end 2030, the aggregate annual volume of all CO2 emissions into the atmosphere (Scope 1, 2 and 3) due to the business operations and sold energy products of the Shell group;

- in the alternative: fails to reduce or cause to be reduced by at least 35% or net 35% relative to 2019 levels, no later than at year-end 2030, the aggregate annual volume of all CO2 emissions into the atmosphere (Scope 1, 2 and 3) due to the business operations and sold energy products of the Shell group;

- further in the alternative: fails to reduce or cause to be reduced by at least 25% or net 25% relative to 2019 levels, no later than at year-end 2030, the aggregate annual volume of all CO2 emissions into the atmosphere (Scope 1, 2 and 3) due to the business operations and sold energy products of the Shell group;

2. to order RDS, both directly and via the companies and legal entities it commonly includes in its consolidated annual accounts and with which it jointly forms the Shell group, to limit or cause to be limited the aggregate annual volume of all CO2 emissions into the atmosphere (Scope 1, 2 and 3) due to the business operations and sold energy products of the Shell group to such an extent that this volume at year-end 2030:

- -

-

principally: will have reduced by at least 45% or net 45% relative to 2019 levels;

- -

-

in the alternative: will have reduced by at least 35% or net 35% relative to 2019 levels;

- -

-

further in the alternative: will have reduced by at least 25% or net 25% relative to 2019 levels;

all of this while ordering RDS to pay the costs of the proceedings.

Milieudefensie et al. have based their claims on the following:

RDS has an obligation, ensuing from the unwritten standard of care pursuant to Book 6 Section 162 Dutch Civil Code28 to contribute to the prevention of dangerous climate change through the corporate policy it determines for the Shell group. For the interpretation of the unwritten standard of care, use can be made of the so-called Kelderluik criteria29, human rights, specifically the right to life and the right to respect for private and family life, as well as soft law endorsed by RDS, such as the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, the UN Global Compact and the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises. RDS has the obligation to ensure that the CO2 emissions attributable to the Shell group (Scope 1 through to 3) will have been reduced at end 2030, relative to 2019 levels, principally by 45% in absolute terms, or net 45% (using the IPCC SR15 report and the IEA’s Net Zero emissions by 2050 scenario as a basis), in the alternative by 35% (using the IEA’s Below 2 Degree Scenario as a basis), and further in the alternative by 25% (using the IEA’s Sustainable Development Scenario as a basis), through the corporate policy of the Shell group. RDS violates this obligation or is at risk of violating this obligation with a hazardous and disastrous corporate policy for the Shell group, which in no way is consistent with the global climate target to prevent a dangerous climate change for the protection of mankind, the human environment and nature.

RDS has put forward a reasoned defence and files a motion for inadmissibility, or to dismiss the claims.

The parties’ assertions are discussed in more detail below, where relevant.