MP 2024/1 - Editorial – foreign subsidies control: Europe first, or fair competition first?

MP 2024/1 - Editorial – foreign subsidies control: Europe first, or fair competition first?

The Foreign Subsidies Regulation (FSR) introduces a new power and tool for the European Commission (Commission) to assess concentrations and is often considered as State aid rules for third countries. Under the FSR, the Commission can assess certain concentrations but also public procurement bids for undue interference from foreign governments and public bodies which have granted foreign financial contributions to the merging or tendering parties. The rationale being that this way the Commission can ensure a level playing field for all parties in Europe. The question remains, however, whether this is a codification of a ‘Europe first’ policy, or whether it is truly the levelling of a skewed playing field.

Introduction

In the past years, we have seen an increasing politization of merger control; not just in the strict sense of merger control based on the EU Merger Regulation or national competition laws, but more holistically in the sense of any type of regulatory scrutiny of concentrations. At the EU’s instigation, there has been a proliferation of foreign direct investment screening regimes (FDI) in Europe, and certain ‘non-notifiable’ concentrations have become notifiable via the regulatory backdoor; with the cherry on the political merger control cake being the entry into force of the FSR.1

The FSR introduces a new power and tool for the Commission to assess concentrations and is often considered as a State aid regime for third countries. Under the FSR, the Commission can assess certain concentrations but also public procurement bids for undue interference from foreign governments and public bodies which have granted foreign financial contributions to the merging or tendering parties. The rationale being that this way the Commission can ensure a level playing field for all parties in Europe. The question remains, however, whether this is a codification of a ‘Europe first’ policy, or whether it is truly the levelling of a skewed playing field.

Over the past years, European companies – national and European ‘champions’ in particular – have complained about unfair competition with certain third country companies, for instance in the airline industry where European airlines compete with (heavily) subsidised Middle Eastern airlines. While the European airlines are subjected to all EU competition rules, including notably the rules on State aid, the Middle Eastern airlines are able to avoid State aid scrutiny. At the same time, notable European transactions have been called to a halt by the Commission, while those industries ‘suffer’ from – what they argue is – unfair competition from foreign companies subsidised by third countries. In 2019, the Commission prohibited the Siemens/Alstom merger, where both Siemens and Alstom – but also the French and German governments – argued that the Commission had not fully appreciated the competition being exerted from heavily subsidised Chinese players. Indeed, it was asserted that the China Railway Rolling Stock Corporation had grown to become the world’s largest railway equipment manufacturer, and – being heavily subsidised by China – was in essence competing unfairly with European champions.

Some have dubbed the FSR as quasi EU-protectionist

Against that backdrop, the Commission started contemplating a potential framework to regulate the interference of foreign subsidies with competition (both within the M&A and public procurement context) in the EU. This ultimately culminated in the current FSR; a framework which some have dubbed as being quasi EU-protectionist. Interestingly, following the adoption and entry into force of the FSR, the Commission’s first in-depth investigation into potentially distortive foreign subsidies is in relation to China Railway Rolling Stock Corporation’s participation in a public procurement procedure in Bulgaria.2

‘History repeats itself, first as tragedy, second as farce’

In the late 19th century and early 20th century, the US and most European economies became increasingly protectionist. Some scholars believe that this resulted in (or at least contributed to), global economic recessions and crises, such as the Great Depression of the 1930s.3 The Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act of 17 June 19304 imposed import tariffs on over 20,000 goods. The Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act hampered international cooperation in a period that was economically and politically perilous and resulted in the decrease in US imports from Europe from a 1929 high of USD 1,334 million to just USD 390 million in 1932, while US exports fell from USD 2,341 million in 1929 to USD 784 million in 1932. Overall, it is estimated that world trade declined by some 66% between 1929 and 1934.5

At the same time, in the UK, Parliament adopted the Import Duties Act of 1932, moving into a protectionist direction. The act placed a 10% tariff on imports, but gave preferential treatment to goods from within the UK Empire in return for concessions on British exports.6 Meanwhile, fascist and communist policies in Europe and across Asia (including in the Soviet Union) also meant the further proliferation of protectionist agendas and policies.

The increasing tendency toward protectionist policies is said by some to have contributed in some shape or form to a global conflict the likes of which the world had never seen before: the Second World War.

Following the Second World War, many countries across the world and especially in Europe and the US started a steady process of liberalisation. In post-war Germany, the Freiburg School and their Ordoliberalism gained traction and were pursued as Germany’s approach to post-war economics. In the US, and other parts of Europe, the Chicago School and their Neoliberalism gained substantial traction and influenced official economy policy.

Ordoliberals advocate for a State-controlled liberal environment, with a healthy level of regulated competition. Ordoliberalism is commonly understood to refer to State controlled market liberalism, a market economy which works within the framework of strong regulation (including competition laws that enshrine market principles). In essence, the State regulates an environment which safeguards fair competition (on the merits) and which prevents the creation of monopolies or oligopolies. According to Ordoliberal theory, the State should not run and direct economic processes (such as under the fascist or communist doctrines that came before it), but should provide sufficient parameters to regulate and control free market reign.7

Neoliberals, on the other hand, are a strong advocate for complete liberalism with as little government interference in and regulation of the economy as possible. Neoliberalism is commonly understood to refer to market functioning without government interference such as tariff controls, low trade barriers and privatisation of the economy, however, it is also a term used interchangeably and progressively with other types of neoliberal theorems (often not being defined at all).8 Neoliberalism gained traction in countries which ‘experienced periods of radical market reform, such as the United Kingdom during the Margaret Thatcher era, the United States under Ronald Reagan, and Chile under Pinochet’s reign.’9

Following a period of nationalism and protectionism, many economies adopted liberal policies (such as Ordoliberalism and Neoliberalism). From the Thatcher, Reagan and Deng Xiaoping administrations to the Blair and Clinton administrations, the total number of protectionist interventions decreased and was at an all-time low in modern history.

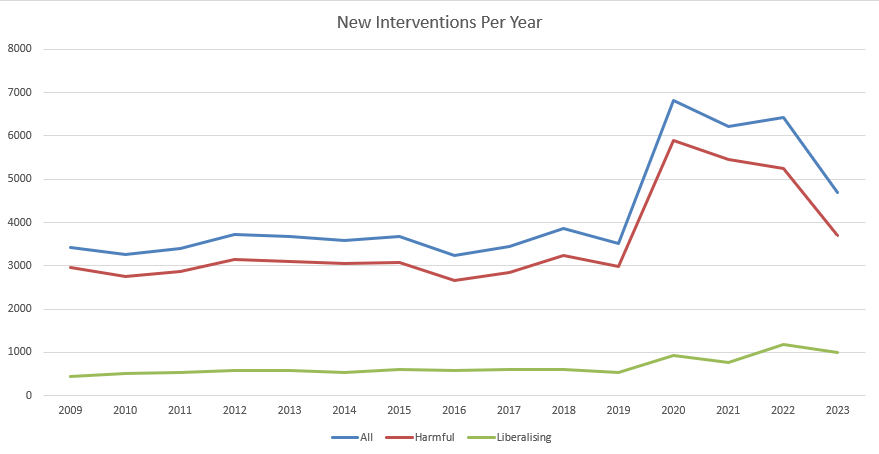

Since 2018/2019, harmful State interventions have increased exponentially

However, note the prescient words of Karl Marx: ‘History repeats itself, first as tragedy, second as farce’. In recent times, protectionist measures have once more gained traction and increased exponentially. According to Global Trade Alert, an association that monitors State interventions taken since November 2008 that are likely to affect foreign commerce,10 since 2018/2019 harmful State interventions have increased exponentially, as illustrated by the table below, based on their data.

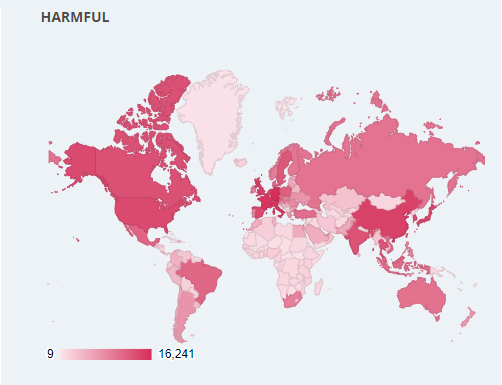

The increase in harmful – and thus protectionist – policies is illustrated in the chart below. The chart clearly shows the degree to which harmful protectionist policies are on the rise in the West (notably the US, Canada and Europe) and the increasingly important BRICS12 countries (some of which have been in trade disputes with these Western countries during this period).

Although the data suggests that we might already be in a farcical era, let’s hope that we are not part of a repeat of history by imposing various policies and regulations (including the FSR), because as French economist Frédéric Bastiat once said: ‘When goods do not cross borders, soldiers will.’

Europe first? Or fair competition on the merits first?

According to the first recital of the FSR: ‘A strong, open and competitive internal market enables both European and foreign undertakings to compete on merits.’14 Indeed, the FSR is part of a package of measures intended to level the playing field between EU operators and their competitors from third countries (and in part protect European champions and Europe’s crown jewels).15

The Commission and EU legislature emphasise that the intention and rationale behind the FSR is to ensure a level playing field while remaining fully open for business, including from abroad. They point to alleged and apparent distortions of competition as a result of foreign subsidies, and the role the FSR can play to close the regulatory gap in that respect.

From a substantive perspective, the FSR’s impact may be limited

Although European champions and other businesses responded positively to the initial proposal for the FSR, after the draft FSR was put to public consultation, a number of businesses were skeptical or criticised the draft regulation (pointing toward the increase in red tape and bureaucracy, fearing many and unworkable notifications).

After the first 100 days of the FSR, it seems that the Commission has received almost twice as many notifications as they expected for the entire year; 52 (pre-)notified cases compared to the 30 expected notifications in total. According to the Commission’s policy brief, these cases cover a large set of sectors ranging from basic industries to fashion retail and high tech. Fourteen cases have been notified formally and nine have been fully assessed. In one of the cases, the notifying parties decided not to proceed with the transaction and therefore abandoned the case during pre-notification.16 It is unclear whether the aborted transaction is related to the scrutiny under the FSR. The Commission does, however, note that in the first 100 days it has not identified any indications regarding the presence of a distortive foreign subsidy that would warrant the opening of a Phase II investigation.17

On balance, it seems as though the impact of the FSR from a substantive perspective may be limited and is indeed intended to ensure a level playing field, rather than to pursue a protectionist Europe first policy.

This special FSR edition of Mededingingsrecht in de Praktijk contains six articles that deal with the entire scope of the FSR. Martijn de Grave and Yvo de Vries have interviewed one of the architects and leading figures of the FSR, Eddy De Smijter (the future head of one of the three units within the FSR Directorate). In the interview, De Smijter provides interesting background to the FSR and the Commission’s current thinking. In the second article, Yvo de Vries and Arnoud de Best provide a brief lay of the land on the FSR and discuss the origins of the regulation. Vanessa van Weelden, Justyna Smela Wolski and Fabian Bickel discuss the – what they call – ‘third wheel of regulatory reviews’ and focus on the implications of the FSR on M&A transactions, while including useful and practical guidance for notifying parties. Greetje van Heezik, Daan Broeckhuijsen and Olav de Wit discuss the FSR from the public procurement perspective and try to answer the question whether it is an effective tool to ensure fair competition, or a paper tiger. Finally, Wessel Geursen discusses in detail the notions of ‘foreign’ and ‘subsidy’ under the FSR and how they relate to basic notions of EU State Aid and the EU Basic Anti-Subsidy Regulation.

This editorial was finalised on 10 March 2024.